As a master’s student in a social work program, you likely didn’t expect to take a course on evaluation. I am guessing that you are likely approaching your evaluation course with trepidation or even irritation. To assist you in adjusting to the reality that you have to take an evaluation course, you may want to start thinking of this course as a social work practice course that focuses on how to evaluate interventions used by social work practitioners.

OK, so maybe you will buy into the concept of practice evaluation, and maybe you will not. You may also be thinking that this is just another research course, but actually it is important to understand that research and evaluation are distinct concepts. Research seeks to explore phenomena to build generalizable knowledge on a subject, whereas evaluation seeks to determine the efficacy of practice in a particular social work intervention context. Efficacy, in this case, refers to the ability of an intervention to produce a desired or intended result. Evaluation projects use research methods to obtain information about an intervention’s efficacy.

Now that we have that clear, let’s talk about the focus of this book, which you can think of as a primer. A primer is a simple introduction to a topic, as opposed to a more in-depth, technical and theoretical textbook.

This primer is designed to support you in understanding the basics of practice evaluation techniques in a language that makes sense to you. Each chapter provides a simple orientation to the topic of the week in your course, which will be supplemented by additional practice evaluation-relevant readings, your professor’s lectures, video screencasts and in-class activities. So, let’s start simply.

Practice evaluation has two parts, the analysis of the efficacy of practice with clients (or client systems, such as groups, or communities) and the critical interpretation of practice evaluation results.

The analysis of practice efficacy involves the careful collection and analysis of client data (quantitative and/or qualitative). The critical consumption of evaluation results requires ‘fluency’ in interpreting basic statistical data as well as rigorous qualitative data analyses. In order to be ethical practitioners, social work practitioners need to be both practice evaluators and critical consumers of evaluation data.

“I didn’t sign up for this,” you may be saying, “I signed up to work with people, not numbers!” And work with people you will, but our profession’s Code of Ethics, (created and voted upon by practitioners nationwide) requires us to evaluate our practice.

National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics: Commentary on research and evaluation as it relates to ethical social work practice

1. Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities to Clients

1.04 Competence (c) When generally recognized standards do not exist with respect to an emerging area of practice, social workers should exercise careful judgment and take responsible steps (including appropriate education, research, training, consultation, and supervision) to ensure the competence of their work and to protect clients from harm.

4. Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities as Professionals

4.01 Competence (a) Social workers should accept responsibility or employment only on the basis of existing competence or the intention to acquire the necessary competence.

(b) Social workers should strive to become and remain proficient in professional practice and the performance of professional functions. Social workers should critically examine and keep current with emerging knowledge relevant to social work. Social workers should routinely review the professional literature and participate in continuing education relevant to social work practice and social work ethics.

5. Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities to the Social Work Profession

5.01 Integrity of the Profession (a) Social workers should work toward the maintenance and promotion of high standards of practice.

(b) Social workers should uphold and advance the values, ethics, knowledge, and mission of the profession. Social workers should protect, enhance, and improve the integrity of the profession through appropriate study and research, active discussion, and responsible criticism of the profession.

(c) Social workers should contribute time and professional expertise to activities that promote respect for the value, integrity, and competence of the social work profession. These activities may include teaching, research, consultation, service, legislative testimony, presentations in the community, and participation in their professional organizations.

(d) Social workers should contribute to the knowledge base of social work and share with colleagues their knowledge related to practice, research, and ethics. Social workers should seek to contribute to the profession’s literature and to share their knowledge at professional meetings and conferences.

(e) Social workers should act to prevent the unauthorized and unqualified practice of social work.

5.02 Evaluation and Research (a) Social workers should monitor and evaluate policies, the implementation of programs, and practice interventions.

(b) Social workers should promote and facilitate evaluation and research to contribute to the development of knowledge.

(c) Social workers should critically examine and keep current with emerging knowledge relevant to social work and fully use evaluation and research evidence in their professional practice.

(d) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should carefully consider possible consequences and should follow guidelines developed for the protection of evaluation and research participants. Appropriate institutional review boards should be consulted.

(e) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should obtain voluntary and written informed consent from participants, when appropriate, without any implied or actual deprivation or penalty for refusal to participate; without undue inducement to participate; and with due regard for participants’ well-being, privacy, and dignity. Informed consent should include information about the nature, extent, and duration of the participation requested and disclosure of the risks and benefits of participation in the research.

(f) When using electronic technology to facilitate evaluation or research, social workers should ensure that participants provide informed consent for the use of such technology. Social workers should assess whether participants are able to use the technology and, when appropriate, offer reasonable alternatives to participate in the evaluation or research.

(g) When evaluation or research participants are incapable of giving informed consent, social workers should provide an appropriate explanation to the participants, obtain the participants’ assent to the extent they are able, and obtain written consent from an appropriate proxy.

(h) Social workers should never design or conduct evaluation or research that does not use consent procedures, such as certain forms of naturalistic observation and archival research, unless rigorous and responsible review of the research has found it to be justified because of its prospective scientific, educational, or applied value and unless equally effective alternative procedures that do not involve waiver of consent are not feasible.

(i) Social workers should inform participants of their right to withdraw from evaluation and research at any time without penalty.

(j) Social workers should take appropriate steps to ensure that participants in evaluation and research have access to appropriate supportive services.

(k) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should protect participants from unwarranted physical or mental distress, harm, danger, or deprivation.

(l) Social workers engaged in the evaluation of services should discuss collected information only for professional purposes and only with people professionally concerned with this information.

(m) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should ensure the anonymity or confidentiality of participants and of the data obtained from them. Social workers should inform participants of any limits of confidentiality, the measures that will be taken to ensure confidentiality, and when any records containing research data will be destroyed.

(n) Social workers who report evaluation and research results should protect participants’ confidentiality by omitting identifying information unless proper consent has been obtained authorizing disclosure.

(o) Social workers should report evaluation and research findings accurately. They should not fabricate or falsify results and should take steps to correct any errors later found in published data using standard publication methods.

(p) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should be alert to and avoid conflicts of interest and dual relationships with participants, should inform participants when a real or potential conflict of interest arises, and should take steps to resolve the issue in a manner that makes participants’ interests primary.

(q) Social workers should educate themselves, their students, and their colleagues about responsible research practices.

But this is not a new phenomenon, for decades, the lack of effectiveness in social work practice was the rule rather than the exception (Fischer, 1978). This has had the potential to hurt our credibility in comparison to the other helping professions who are doing better in this regard. This reality is also what has led us to begin to embrace the use of evidence-based practices, and to increase our efforts at studying social work interventions altogether.

Despite this, at least one large research study found that 75% of licensed social workers reported using at least one scientifically unsupported intervention in their work and many NASW-sponsored continuing education workshops featured non-evidence-based practices (Pignotti and Thyer, 2009). Further, fewer than 25% of social workers evaluate their own practice using rigorous techniques (Baker, Stephens & Hitchcock, 2010).

In the face of this depressing information, the truth is, we have to remember that evaluating practice makes us better practitioners – practitioners who are learning and growing and reflecting through the collection and consumption of evaluation data to inform what we do with clients. As a matter of fact, you are likely already doing some of this practice evaluation work in your internships without knowing it! Let me tell you more.

When thinking about evaluating practice, it is helpful to distinguish between two types of evaluation: implicit and explicit (Davis, Dennis & Culbertson, 2015). Implicit evaluation involves an informal-interactive approach that can include consultation with colleagues, supervision from a supervisor or use of informal client feedback. Explicit evaluation, on the other hand, consists of a range of approaches that are more formal and analytic. These approaches can include single client evaluations or evaluations of groups of clients – either of which can look at specific intervention processes or outcomes, among others.

By using *both* implicit and explicit forms of practice evaluation, we can become reflective and reflexive social work practitioners. Reflectivity is about unearthing the actual truth embedded in what professionals do, versus just what they *say* they do (Schon, 1983, 1987). Reflexivity, by contrast, is the ability to look inwards and outwards to recognize how society and culture impacts practice as well as how we ourselves influence practice.

As a reflective and reflexive social work practitioner, you will want to ask yourself “How do I create and influence the knowledge about my practice that I use to make decisions?” In embracing reflectivity and reflexivity, we move beyond ‘just knowing,’ which is a form of implicit evaluation that is subjective by nature. By embracing both explicit and implicit evaluation, we start to see that what we are doing with our clients is delving into the realm of evidence-based practice. So, let’s talk about that phenomenon.

On evidence-based practice as a process

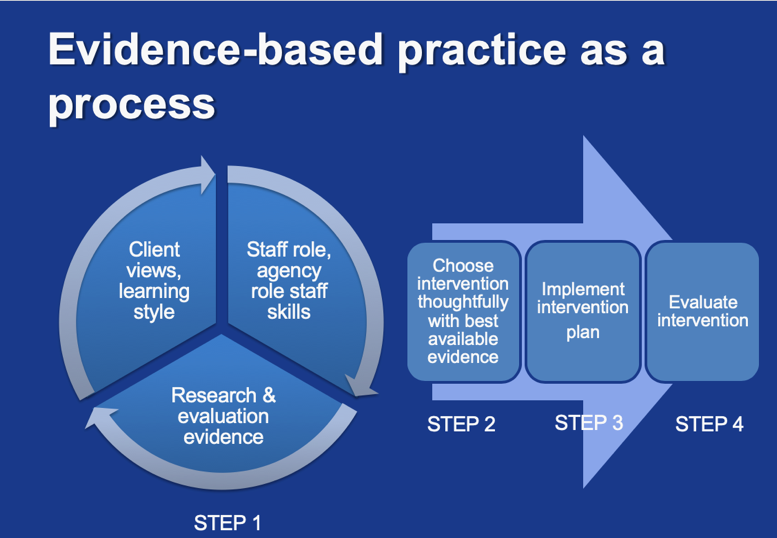

Evidence-based practice, conceptualized as a process (not a thing) of practitioner data consideration, choice of intervention, intervention implementation and practice evaluation, is the direction the social work profession has embraced for the future (informed by Gambrill, 1999). I conceptualize this process as having four steps, which are pictured in Figure 1.1. Let’s walk through those steps.

Figure 1.1 Evidence-based practice as a process

Step One: The consideration phase

In this step, practitioners take stock of their client’s presenting problem, learning style, and hopes for treatment. Adding to this, the practitioner considers their organizational mandate (what they are tasked with doing by their employer) as well as their professional skills and capacities (what they are trained to do, what they need training to do).

These two items are weighed against a consideration of the data related to the population and presenting problem, namely professional reports on practice evaluation. This tripartite consideration process allows you to weigh the available evidence about a population and presenting problem with your skill set while thinking about the utility of that approach with the client in question.

The deconstruction-reconstruction process

This consideration process that we are talking about is referred to as “deconstruction-reconstruction” (Pollio, 2006). In fact, social workers “are encouraged to be knowledgeable about findings from a variety of studies, integrating them while taking into consideration clinical experience and judgement” (Nevo and Slonim-Nevo, 2011, 1193). This is a vital point, as critics of evidence-based practice often worry that clinical experience and clinical judgement are edged out of the process. That couldn’t be farther from the truth.

During the deconstruction-reconstruction process, practitioners will want to be mindful of professional guidelines for how much existing evidence is enough to go on. The American Psychological Association (1996), states that ‘enough evidence’ is one of two conditions:

First, you need two group evaluations demonstrating efficacy superior to a placebo or other treatment or equivalent to already-established treatment in research with adequate statistical properties and power. Second, an alternative would be the presence of nine individual case studies demonstrating efficacy in comparison to another treatment.

When I say you need to meet one of these two conditions, I do not mean you need to conduct these yourselves necessarily – the intent behind setting out these minimal guidelines as I understand it is that clinicians would look for that level of evidence in the literature before determining something is an empirically-supported intervention.

Steps Two and Three: Drawing on the best-available evidence to choose an intervention

After going through the deconstruction-reconstruction phase, the practitioner and client are to choose an intervention from the best available evidence, and put it into place.

Step Four: Practice evaluation

At this point, the evaluation phase commences, which should ideally collect data on both the process of treatment and the outcome of treatment. We call these ‘process measurements’ and ‘outcome measurements.’ Alternatively, these are called formative and summative measures.

By measurement, we are referring to a structured way to collect quality information about attitudes, knowledge, behaviors or symptoms in a consistent manner. Evaluators refer to this as operationalizing process and outcome concepts.

In order to operationalize concepts, our field prefers the rigor of using standardized measures (i.e. questionnaires, indices, instruments, tests, basically lists of questions that together conceptualize a clinical concept, such as self-esteem, depression or anxiety) which are accepted by professionals in the field, versus the use of untested unstandardized measures. In addition to standardized measures, social workers often use behavioral measures, such as a client’s accounting of days of sobriety.

A process measurement might consider a client’s attendance in a program or whether a practitioner is sticking close to the therapeutic intervention that was chosen as the weeks went by. An outcome measurement might consider a client’s sense of self efficacy or level of anxiety at the beginning, middle and end of the intervention. Even though we would collect the measurement with a focus on the outcome, or last measurement, we would want to compare with the beginning and the middle as well.

Can you see how both measurements might be useful for your practice? Using process and outcome measures are important tasks for engaging in the evaluation step of evidence-based practice as a process. Let’s imagine evaluating client progress as akin to a daffodil blooming in early spring (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Spring bulbs: An evaluation metaphor

As you can see, the daffodil bulb goes from a newly sprouting bulb underground all the way up to a fully flowering bulb over-ground. This mimics the process of a client’s ideal response to a social work intervention, responses which unfold over time. The left three images of the bulb’s growth can be thought of as the time when you would collect process measures. The final image, on the right, can be thought of as the time when you would collect an outcome measure, at the end of the intervention, or after.

Moving beyond the ‘case mentality’

In embracing process and outcome measurement for practice evaluation, we are evolving away from what is known as a case mentality. Evidence based practice as a process has emerged in the social work profession after almost a century of evaluating practice subjectively, primarily through the use of implicit evaluation. Our profession is now moving beyond what Royse, Thyer and Padgett (2016) refer to as a ‘case focus’ or ‘case mentality,’ where we focus solely on the immediate case before us.

When using this ‘case mentality,’ we are not, for example, aggregating (i.e. drawing together) data at the individual or group level to determine effectiveness in an objective manner (or, in a manner that is as objective as is possible). Instead, by engaging in the process of evidence-based practice, we embrace the *addition* of an explicit evaluation approach. This allows for the development of verifiable evidence with as-objective-as-possible, operational definitions that complements implicit evaluation. Through this form of engagement in practice, we move away from the solo embrace of subjective, implicit evaluations.

In order to embrace our ethical duty to evaluate practice, we need intervention techniques that feel right to us clinically, while simultaneously possessing scientific rigor. While moving towards embracing the process of evidence-based practice, we need approaches to evaluation that feel relevant to practice that occurs in what are often messy contexts. We also need real, substantive involvement from social work practitioners in designing practice evaluation as part of the process of evidence-based practice, as this will help with buy-in. But we also need for practitioners to be able to understand and critique evaluation data in order to better their intervention approaches.

At this point, you may still be asking yourself “OK, but is it *really* necessary to study practice evaluation? Can’t someone else do this work?” There are at least two answers that come in response. The first question comes in the form of a question: do clients have a right to effective treatment that is measured objectively? Most of my students usually say yes, simultaneously recognizing that they are not currently engaging in that practice! The second question recognizes our ethical duty to provide informed consent before treatment, informing our clients of risks, benefits and alternatives to the intervention suggested. Both of these conditions require social workers to have practice evaluation skills.

So, maybe I have convinced you of the need for practice evaluation skills, and maybe I have not. Regardless, the following chapters will provide you with the take home messages you need to engage in practice evaluation and the critical consumption of evaluation data.

Looking ahead, at the end of this course, you will be able to engage in the four principles of evidence-based practice (Pollio, 2006):

- Explain the evidence clearly

- Create an evaluation plan that yields useful data for being responsive to the client

- Be able to re-choose or refine intervention and evaluation efforts based on data collected

- Be aware of relevant evidence on techniques

Discussion questions for the introduction

- Why do we need both implicit and explicit evaluation co-exist in social work practice?

- How can implicit and explicit evaluation co-exist in social work practice?

- How does the process of evidence-based practice relate to the conduct of practice evaluation?

- How do reflexivity and reflectiveness relate to practice evaluation?

- Choose a population and an intervention. Do a quick literature search in the academic databases and narrate your deconstruction-reconstruction process based on your findings.

References for the introduction

Baker, L., Stephens, F. and Hitchcock, L. (2010). Social work practitioners and practice evaluation: How are we doing? Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 20: 963-973.

Davis, T., Dennis, C., and Culbertson, S. (2015). Practice evaluation strategies among clinical social workers: New directions in practice research. Research on Social Work Practice. 25(6), 654-669.

Fischer, J. (1973). Is casework effective? Social Work. 18, 15-20.

Gambrill, E. (2003). Evidenced Based Practice: Sea Change or the Emperor’s New Clothes? Journal of Social Work Education, 39(1), 3-23.

Pignotti, M., & Thyer, B. (2009, March). Use of novel unsupported and empirically supported therapies by licensed clinical social workers: An Exploratory Study. Social Work Research, 33(1), 5-17.

Pollio, D. (2006). The art of evidence-based practice. Research on Social Work Practice. 16(2), 224-232.

Royse, D., Thyer, B. and Padgett, D. (2016). Chapter 1: Introduction. In Eds. Royse, D., Thyer, B. and Padgett, D. (2016). Program evaluation: An introduction to an evidence-based approach, sixth edition. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Schon, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. London: Temple Smith.

Schon, D. (1987) Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.